The Washdyke by Bill Goodhand

In this article Bill Goodhand describes the process of washing sheep before shearing, and how this process took place in Welbourn in the area known as the Washdyke.

Prior to World War II, most farmers who were about to clip their flock would have first washed their sheep in a local stream in order that the fleece could be sold in a better condition and for a higher price. Normally this arduous and repetitive task would be carried out about a fortnight before shearing (not to be confused with sheep dipping to prevent parasites and sheep scab) in order to allow the natural grease to return to the wool and for the fleece to frizz out and assume its normal texture. Indeed sheep washing has been a long standing practice in English agriculture as is recorded by Thomas Tusser who wrote a treatise on agriculture in Elizabethan times. His ‘June Husbandrie’ aptly sums up the business of sheep washing: –

Wash sheep – for the better – where water doth run,

And let him go cleanly and dry in the sun;

Then shear him. And spare not, at two days an end,

The sooner the better his corps will amend.[1]

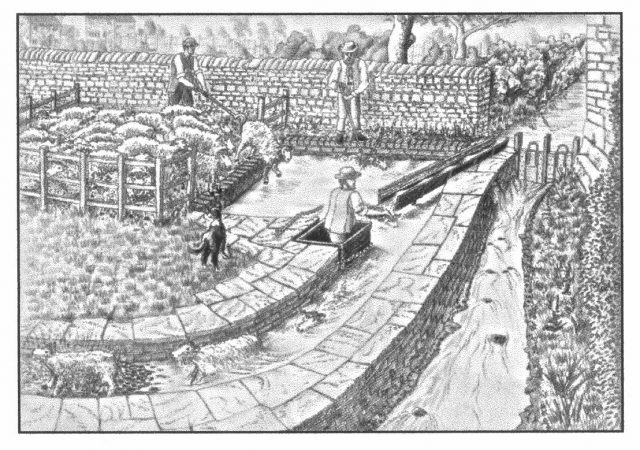

In the past Welbourn was a notable location for washing sheep given that there was a constant supply of pure spring water in streams leaving The Beck. During the early summer flocks of sheep were brought along the local lanes into the village from all outlying farms including many in the neighbouring parishes for this purpose. In the area known as the Washdyke, close by the former White Horse Public House, the water was led off the dyke into a large pit with a wooden shoot[2] at one end. Either side of the shoot were two barrels anchored to the stream bed by stout stakes, each with a man in place. As the sheep were thrown into the pool, long poles were used to then push the sheep towards the barrels where the two operatives would grab each animal in turn and hold it under the torrent of water. It was essential that each sheep was first ‘breasted’, that is, its underside was washed thoroughly before being turned on its back to complete the process: a wet, cold, and smelly experience both for man and beast. The flocks of sheep awaiting their turn were placed in permanent pens which ran up to the wall of the White Horse Pub where the drovers could also put up for the night before walking the flocks back to their farms.

This colourful and noisy burst of seasonal farming activity within the village was particularly popular with the local children early in the 2oth century. The late Fred Bird remembers that the village lads would rush home from school at midday, gobble their dinners and then tear back to ‘help’ throw the sheep into the washing pit. The reluctant return to afternoon school by a crowd of damp, smelly children was far from popular with the head teacher, Mr Tommy Taylor. In truth, Mr Taylor would also have been concerned about the danger to his young charges of playing near the Washdyke, as evidenced by his sad entry of 16th June, 1923, in the school logbook.

“Herbert Whydle aged five was drowned in the Washdyke after he had been seen playing on the bank. Half an hour later he was taken from the water apparently dead and did not respond to artificial respiration.”

The Washdyke was immediately declared out of bounds to the school children.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Musson family who owned the land and the equipment for operating the sheep wash, sold the property ot Stanley Overton who filled in the Washdyke pit and used the site to repair tractors and grass cutting machinery to maintain the neighbouring RAF airfields. Later, Harold Overton had the premises for his popular lawnmower sales and servicing business. More recently, the site was developed for housing. So ended a longstanding farming tradition in Welbourn dating back in all probability to at least the 17th Century when the parish records frequently list the related occupations of shepherd, weaver and tailor in the village. Even within living memory, large numbers of sheep were being raised on local farms, for example in 1910 there were almost 15,000 sheep in the cliff villages between Boothby and Leadenham, including 2,300 in Welbourn parish. Notably, each of these parishes contains a large area of the limestone heathland once regarded as prime sheep country. Small wonder that Joseph Patchett of Welbourn could record his occupations as butcher and sheep dipper in the 1901 census, which also records an ‘A.Drover’ staying at staying at The White Horse! By 1938 the numbers of sheep in Welbourn parish had fallen sharply to 850, this decline continuing as a result of the remaining grassland going under the plough during World War II in order to grow more crops to feed the nation.

Today there are no permanent flocks of sheep in the parish and in any case no farmer bothers to wash the sheep before shearing.

n.b. Early in the 20th Century many of the flocks would have been of the once popular Lincolnshire Longwool sheep, highly regarded for their thick, heavy fleeces. Sadly this breed is now a rarity on our farms.

Thanks to Jack Harmston and the later Fred Bird for their personal memories of the old Welbourn sheep wash and Washdyke.

Map taken from OS 1:2500. 1887

David Hopkins’ illustration of an old sheepwash fom the Newsletter of the Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire, Spring 2006.

Welbourn Washdyke by Bill Goodhand was first published in Two Villages magazine

[1] Thomas Tusser’s poem was taken from ‘Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay’ by Gavin Ewart Evans.

[2] Older English spelling of chute